Clothing the Celts

Posted by Lanea on Saturday, July 22nd, 2006

There’s been a trend lately, wherein knitters take up sewing. Lovely aprons and skirts and summery tops are popping up all over the blog-o-sphere. Grand!

Which makes me think, maybe not all of the new stitchers have been given all of the secrets. I started sewing costuming when I was 14. By 16, I was pretty darn good at it. Once I got into college, Crazy Lanea’s was firmly established as a time-shredding hobby. And since it’s crazy sewing season for me, I figured I should share some of what I know and show you all how I work. So here goes.

Step one: Buy good fabric.

- I know it seems obvious, but beautiful hand- and machine-sewing is almost entirely dependent on the quality of fabric you’re working with. Just about every sewing disaster starts with bad fabric (except when the sewer in question has some machine killing curse).

- Since I make primarily historic costuming for myself and for my friends, I work almost exclusively in linen, wool, silk, cotton, and blends thereof. Those fabrics were all available to the wealthiest insular Celts in the part of the Iron Age we recreate, and they are all wonderful to work with, so we use them. Natural fabrics wear well, they’re washable (I promise–we’ve been washing wool for thousands of years), they take dyes beautifully, they breathe well, and they feel good in the hand and against the skin.

- Perhaps more importantly, because the clothes I make are worn either in hot weather or around fires much of the time, it’s important that I not encase my loved ones in anything that will keep their sweat from evaporating or melt if briefly exposed to fire. No acrylic, no nylon, no poly, nothing made from petrochemicals. Never ever ever.

- If you are sewing for children, please don’t dare make anything from melt-able synthetics, I beg you.

Step two: Since you’re already at the fabric shop, buy a freaking drawstring pants pattern, already.

- I make a lot of pants, in part because many people I know have terrible luck making their own pants because they refuse to buy commercial pants patterns. Don’t be silly, folks. Pants patterns are cheap, and since we’ve already broken the rules by using commercially made fabrics that are woven on looms far wider than the Celts used and dyed with chemical dyes, using a pattern is no cop out. There is a special little trick to making the crotch of a pair of drawstring pants, and Butterick or McCalls will teach you that trick four $4. The curve at the front and the curve at the back are different. I promise you. And it’s hard to duplicate the curve correctly without a pattern.

Step three: Buy the right tools and notions.

- Make sure to get good thread. Your seams will last longer. What thread you need to buy depends on what sort of fabric you’re using. When in doubt, talk to someone who works at the store.

- Get good shears, and don’t use them on paper or leather. Your hands will thank you.

- Buy some tailor’s chalk–it is incredibly useful.

- Get good pins, and lots of them, in a few sizes. You must must must pin things.

- Get and use an iron and an ironing board if you don’t have them already. Whattareya, raised by wolves?

- Get some good small needles for hand-sewing. Thou shall not machine-hem clothing for living history.

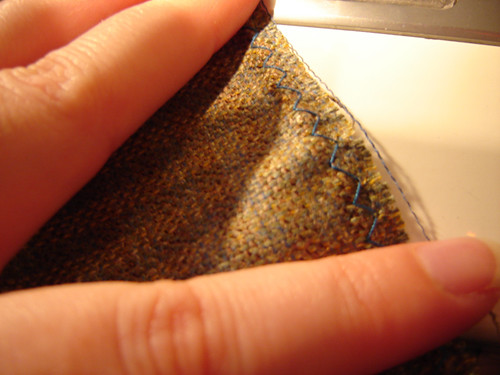

- That seam will save you money and time.

- You will lose much less fabric to fraying; fabrics will get less knotted up on the dryer, and thus dry more quickly; and it will be easier to iron everything later. Linen is particularly fond of fraying.

- I experimented last year–I bought two 3-yard pieces of linen in the same weight from the same source. One I tossed in the wash without that quick line of stitching, the other I sewed up, proper like. I dried both in the dryer, and then pressed them. The one I sewed first was 2 and 3/4 yards once it was pre-shrunk and pressed. The other one? 2 and 1/4. $5 gone into the trash and the lint filter. For a person like me who makes probably 30 garments a year, that’s $150 plus wasted.

- To make matters worse, all of that frayed mess that comes off fabric you don’t bother to prep may decide to either destroy your washer’s motor or clog up your waste-water line.

- Also, yes, I am telling you to prewash all of your fabric, no matter what the label says. All of it. Yes, the silk. Yes, the linen, and certainly the wool. Your wool will full a bit. That’s good. That’s what both Celtic and Viking weavers did with their woolens. They were smart about fabric, because it was so much more valuable to them than it is to us.

- Once it’s all clean, machine dry all of your fabric that is not woolen. Yes, I said it–throw everything but the wool in the dryer. Treat it roughly before you put any effort into cutting and sewing.

Step five: Pull your fabric out of the dryer when it is still damp and iron it immediately.

- It will be much easier to press, and all of your prep work will be done.

- If you decide to take a break from sewing and the break lasts four months, you’ll be able to start cutting knowing that all of the boring stuff is already taken care of.

- If you’re working with wool, line dry it until it’s fully dry, and then press it lightly.

Step six: Think before you cut.

- Think a lot. What’s cut cannot be uncut.

- Consult decent patterns or costuming resources before you do anything drastic.

- Get good measurements of yourself or your

victimsubject. It doesn’t matter how well you can sew if you can’t fit a garment. - Find the grain of your fabric. If you’re new to sewing or your eyesight isn’t great, mark the horizontal and vertical grain with your tailor’s chalk. Cutting pieces off-grain will cause you lots of problems later on–patterns won’t line up, hems will never be straight, you’ll get funny puckering where you don’t want it.

- If you’re using a pattern or a finished garment as a template, give some thought to the most efficient or appropriate way to lay out your piece before you cut. If you’re using a pattern, you’ll need to figure out how to match it up before cutting.

- Make sure you are leaving yourself decent seam allowances, particularly when working with fabrics that like to fray. Linen really likes to fray.

- Also think about whether you intend to wear the garment against your skin or as an outer layer. If it’s likely to be layered over other pieces, give the pieces extra ease.

- If you’re making a tunic or dress, remember to leave enough fabric for a neck facing. Neck facings are grand things. Use them.

Step seven: Think some more before you cut.

Step eight: Cut safely and cleanly.

- Keep your pets away from your cutting surface. If your cutting surface is the floor, vacuum it before you lay out your fabric.

- Lay out your pattern pieces carefully and pin them in place. If you’re not using a pattern, draw out your shapes with tailor’s chalk, making sure to pay attention to the grain, to any stretching that may occur as you draw, and to any folds and selvages.

- Before cutting, look at the pattern pieces or drawn cutlines carefully from several points of view. Stand back from your work and look some more.

- Keep your fingers out of the way of your shears. Seriously. Lots of people cut themselves badly while cutting out fabric. Don’t do it–it ruins the fabric.

- Make sure you are about to cut the right number of backs and fronts, the right number of sleeves and legs, the right number of facings, etc.

Step nine: Pin pieces together before you start sewing.

- Just trust me, here. Your sewn curves will lie flatter, your pants-legs will match up top and bottom, your hems will be easier.

Step ten: Remember that there is such a thing as a seam that is too strong.

- Many of us want to sew things so strongly that they’ll be indestructible. It’s impossible. Stop thinking that way.

- Think instead of how to sew things so that they can ultimately be repaired.

- If your seams are too strong because you used too heavy a thread or reinforced them too much, when a stress point finally tears, it will be the fabric that fails instead of the seam. It’s no trouble at all to resew a blown seam. It’s a pain in the ass to patch shredded fabric near a seam.

Step eleven, twelve, and thirteen: Press your seams as you go.

- Again, just trust me. It will be much easier for you to sew seam intersections, like those in the crotch of a pair of pants. And your finished garment will lie better against your body. And you will go to heaven.

Step fourteen: Try the assembled garment on before you start pinning up hems.

- Too short is bad.

- Uneven hems are bad.

- Having a friend to help measure and pin up a skirt hem is wonderful. If necessary, bribe a talented sewing friend with baked goods or silk.

Step fifteen: Pin your hems carefully, and sew them by hand.

- I sew hems by hand on almost everything I make, whether or not it’s for living history.

- Machine stitching is ugly and it’s inelastic.

- If you want the hem of a skirt to hang beautifully, sew it by hand.

- If you want people to notice the beautiful texture and color of your silk noil instead of the robotic staccato of machine sewing, sew it by hand.

- If you want a neck facing to lie properly, sew it by hand.

- Hand sewing goes slowly, sure, but that leisurely pace allows you to tweak things ever so slightly in ways you won’t be able to manage while chugging along on a machine.

Step sixteen: If you don’t want to do all that stupid hard work, bribe Lanea to make your clothes.

- I like amber, fabric, yarn, silver, hand-cast bronze things, handmade shoes, money, vacation homes–you can find a way to get me to sew for you.

- Unless you’re a jerk to someone I love, that is. And then there’s no hope for you or your wardrobe, and you will have to buy plaid drawstring pants at Wal Mart and hope for the best. The best will never come. Move far away, gone guys, and don’t come back.

Step seventeen: Be kind to your handmade garments.

- Don’t leave wet garments in a pile to moulder–if something is wet and dirty, hang it up so that it can at least be dry and dirty.

- Use the gentle cycle with cold water to wash them.

- Soak stains out instead of scrubbing them too much. If you’ve got a stubborn stain, consult a stain–removal guide.

- Hang your clothes to dry: it’s good for the clothes, the environment, and your electric bill.

- Don’t leave dark or brightly-dyed fabrics in the sun too long–they’ll sun bleach.

- Don’t use chlorine bleach: bleach eats wool completely away, it yellows linens, and does cruel things to most other natural fibers.

- Don’t wash just a couple of garments at a time in a machine: the less stuff in the tub, the more the stuff gets beaten up.

- Use dye magnets when washing red or blue garments that are relatively new.

- Fix tears and holes as soon as they occur. If I made you something and it’s damaged and you’re not confident about fixing it yourself, ask me to help you.

- Don’t wrestle or fight in any fancy-schmancy stuff I make you, or I’ll cut you off.

Coming soon: A day in the sweatshop.

Filed in sewing,tutorials | 5 responses so far

KnittnLissaon 23 Jul 2006 at 12:01 pm 1Dang, that almost makes me want to sew! Perhaps someday I’ll devise the perfect bribe, for I would so much rather have something that my dear friend made than the result of my lousy-vision-ADD-addled-lazyassed head.

The Purloined Letteron 24 Jul 2006 at 8:26 am 2Excellent and useful! I think you may be giving me the confidence to try it!

Amberon 24 Jul 2006 at 11:05 am 3Thanks for that! What a great post. It doesn’t get any better than cheeky + informative. And that’s a lot of informative. Thanks for the reminder to wash and really machine dry first – I always think things one makes should be wearable and usable and if the fabric can’t take a washing, as pretty or fantastic as it may be, ya just can’t pretend it will make a good garment.

I’m looking forward to seeing your day in the sweatshop!

Junoon 24 Jul 2006 at 12:08 pm 4So you’re saying linen frays?

laneaon 24 Jul 2006 at 12:22 pm 5Crap–I forgot to include a warning about how much linen frays! Hey everyone–linen frays : >